Aerospace Pioneers

Advancements in aerospace are really the sum of achievements by many people. Dreams, ideas, hard work, failure, results, retrying – all contribute to the continuation of knowledge and the ultimate success of an invention, process, or program.

Over the course of history many people have contributed to this advancement of knowledge, whether through research or experimentation. We list only a few of the many notable figures on whose shoulders we stand today.

If there is someone that you feel should be listed here, please contact Lawrence Garrett, AIAA Web Editor, at lawrenceg@aiaa.org.

Pioneer Profiles

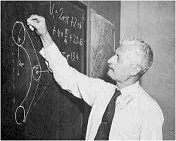

Dr. Robert Hutchings Goddard (Born 5 October 1882 in Worcester, MA – died 10 August 1945

in Baltimore, MD), was an American professor, engineer, inventor, and physicist, who left a lasting legacy within the aerospace community. Known as the father of modern rocketry, as well as the man who ushered in the Space Age, Goddard created

and built the world’s first liquid-fueled rocket. Successfully launched 16 March 1926, his work ignited a new age in space flight and technological innovation. Goddard, along with his team, went on to launch 34 rockets between 1926 and

1941, while reaching altitudes as high as 1.6 miles and speeds up to 550 mph. Two Goddard inventions – a multi-stage rocket and a liquid-fuel rocket, both introduced in 1914, were critical milestones toward achieving spaceflight. Today,

Goddard’s work is credited for having made spaceflight possible.

Dr. Robert Hutchings Goddard (Born 5 October 1882 in Worcester, MA – died 10 August 1945

in Baltimore, MD), was an American professor, engineer, inventor, and physicist, who left a lasting legacy within the aerospace community. Known as the father of modern rocketry, as well as the man who ushered in the Space Age, Goddard created

and built the world’s first liquid-fueled rocket. Successfully launched 16 March 1926, his work ignited a new age in space flight and technological innovation. Goddard, along with his team, went on to launch 34 rockets between 1926 and

1941, while reaching altitudes as high as 1.6 miles and speeds up to 550 mph. Two Goddard inventions – a multi-stage rocket and a liquid-fuel rocket, both introduced in 1914, were critical milestones toward achieving spaceflight. Today,

Goddard’s work is credited for having made spaceflight possible.

It is difficult to say what is impossible, for the dream of yesterday is the hope of today and the reality of tomorrow.

Dr. Robert Hutchings Goddard

Courtesy of the National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution

As America's leading propeller

engineer and designer during the aeronautical design revolution of the 1920s and 1930s, Frank Walker Caldwell (1889-1974) was a significant contributor to the development of propulsion technology. Caldwell oversaw the invention, development,

and innovation of the metal, ground-adjustable pitch propeller and the hydraulically-actuated two-position controllable-pitch and constant-speed propellers during his tenure as the United States government's chief propeller engineer (1917-1928)

and his work in industry (1929-1938). In the process, he pioneered the fundamental propeller testing facilities and techniques needed for successful engineering development.

A native of Lookout Mountain near Chattanooga, Tennessee,

Caldwell received his mechanical engineering degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1912. When the United States entered World War I, Caldwell joined the Propeller Department of the Airplane Engineering Division of the United

States Army Air Service located at McCook Field in Dayton, Ohio, as chief engineer. He was responsible for the research, design, and testing of all aircraft propellers used by the army and navy during the war.

The war accelerated

the development of aeronautical technology. As engine horsepower increased, the American military required heavier, larger, and more complicated propellers. It became clear that the wooden, fixed-pitch propeller, which was only efficient in

one flight regime, would not be adequate. What was needed was a variable-pitch propeller, a propeller able to vary the angle, or pitch, of its blades to meet different performance regimes. Caldwell effectively set the tone for developing a

new propeller that consisted of separate detachable blades joined to a central hub that would allow pitch adjustment on the ground. This ground-adjustable pitch propeller would be a crucial technology to the success of milestone flights such

as Charles A. Lindbergh's solo transatlantic flight in May 1927 even though it was still essentially a fixed-pitch propeller.

Recognizing that the key to performance was the ability to change pitch while in flight, Caldwell joined

the Hamilton Standard Propeller Corporation in 1929 to develop a controllable-pitch propeller. His hydraulic, two-position design provided efficiency at both takeoff and cruise, the two main operating regimes for the airplane. Performance

tests revealed that Caldwell's invention maximized the performance of revolutionary aircraft such as the Boeing Model 247 and the Douglas DC-2. The National Aeronautics Association recognized Caldwell and Hamilton Standard for their achievement

by awarding them the 1933 Collier Trophy.

Caldwell and Hamilton Standard went on to begin development of a propeller that changed blade angle automatically according to engine speed, the Hydromatic constant-speed propeller. A major

feature of this new propeller was its ability to "feather," which positioned the blades to prevent propeller windmilling after engine failure. Virtually the entire air force frontline inventory during World War II, from multi-engine bombers

to fighter and transport aircraft, employed Hydromatic propellers. The feathering feature alone was crucial to the safety of Allied bomber crews over Germany and Japan.

To ensure that these new propeller designs were efficient,

structurally sound, and ready for production, Caldwell developed the propeller whirl test. The test involved mounting a propeller to a stationary test stand where instruments measured the effective thrust of the propeller while it underwent

long endurance runs at high speeds. He designed the whirl-testing facilities for the United States government at McCook Field (1918-1927) and Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio (1926-2000). Caldwell's pioneering testing procedures were indispensable

to the development of all modern high-performance propellers during the twentieth century.

The Institute of Aeronautical Sciences, the present day AIAA, awarded Caldwell the Sylvanus A. Reed Award in 1935 and an honorary fellowship

in 1946. He also served as the institute's president in 1941. During World War II and the early Cold War, Caldwell was the corporate director of the United Aircraft Corporation Research Division until retiring in 1955. On December 23, 1974,

Caldwell passed away at his home in West Hartford, Connecticut, at the age of 85.

Visit the United States on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on American pioneers.

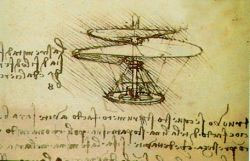

Leonardo da Vinci was born in 1452 in the small town of Vinci, in Tuscany, near Florence. In 1466, Leonardo moved to Florence, where he entered the workshop of Verrocchio. During this time, da Vinci encountered such artists as Botticelli, Ghirlandaio,

and Lorenzo di Credi. Early in his apprenticeship he painted an angel, and perhaps portions of the landscape, in Verrocchio's Baptism of Christ (Uffizi). In 1472, he was registered in the painters' guild and began his artistic career. However, not only was Leonardo a brilliant artist, he was an amazing inventor. Leonardo had many ideas and drawings on different

war machines, flying machines, work machines, water and land machines, and as well as architectural structures. Many years after his death, his drawings and theories were discovered by people who did not realize that he had already designed numerous

machines of the present and the future. Leonardo was a man who loved art, but despised war. This does not mean that the concept of war was not among many of his thoughts. Most of Leonardo's machines had something to do with war. For example a

circular armored car that could shoot three hundred and sixty degrees without turning, a thirty three barreled organ, automatic hull rammer, multiple cross bows, and many more. Leonardo also had some of the earliest ideas on flight. One of the

most well known ideas of Leonardo's flying machines was the aerial screw. This contraption has been classified as the helicopter's ancestor. The aerial screw has almost the same concept of the helicopter. The prop of the aerial screw is a flat

screw, and when turned it would create lift. Some of Leonardo's inventions were not tested in his time, because he would move on the other projects; the aerial screw was one of these inventions that were left untested. (Image 1: Manuscript B,

folio 83 v. )

However, not only was Leonardo a brilliant artist, he was an amazing inventor. Leonardo had many ideas and drawings on different

war machines, flying machines, work machines, water and land machines, and as well as architectural structures. Many years after his death, his drawings and theories were discovered by people who did not realize that he had already designed numerous

machines of the present and the future. Leonardo was a man who loved art, but despised war. This does not mean that the concept of war was not among many of his thoughts. Most of Leonardo's machines had something to do with war. For example a

circular armored car that could shoot three hundred and sixty degrees without turning, a thirty three barreled organ, automatic hull rammer, multiple cross bows, and many more. Leonardo also had some of the earliest ideas on flight. One of the

most well known ideas of Leonardo's flying machines was the aerial screw. This contraption has been classified as the helicopter's ancestor. The aerial screw has almost the same concept of the helicopter. The prop of the aerial screw is a flat

screw, and when turned it would create lift. Some of Leonardo's inventions were not tested in his time, because he would move on the other projects; the aerial screw was one of these inventions that were left untested. (Image 1: Manuscript B,

folio 83 v. )

Another piece of ingenious from Leonardo was the parachute. The only difference between the ones today and his is that he used a temple like structure for the parachute. Leonardo had many ideas for gliders, and also a drawing of a leaf spring engine for flying machines. Some of Leonardo's concepts are being used today, of course with a few modifications, for example the scuba diving suit.

Leonardo's thoughts and theories have had an impacted on our world today. With out Leonardo's ideas

we might not have been where we are today. We could have been still trying to find out how to break the sound barrier, because Leonardo would have not inspired the early scientist like Otto Lilienthal. Without Otto Lilienthal the Wright brothers

who not have read that nine-page article on Lilienthal in the September issue of McClure's Magazine. (Image 2: Codex Atlanticus, folio 1058 Drawing from Il Codice Atlantico di Leonardo da Vinci nella biblioteca Ambrosiana di Milano, Editore Milano

Hoepli 1894-1904)

Leonardo's thoughts and theories have had an impacted on our world today. With out Leonardo's ideas

we might not have been where we are today. We could have been still trying to find out how to break the sound barrier, because Leonardo would have not inspired the early scientist like Otto Lilienthal. Without Otto Lilienthal the Wright brothers

who not have read that nine-page article on Lilienthal in the September issue of McClure's Magazine. (Image 2: Codex Atlanticus, folio 1058 Drawing from Il Codice Atlantico di Leonardo da Vinci nella biblioteca Ambrosiana di Milano, Editore Milano

Hoepli 1894-1904)

Provided to the AIAA for the sole purpose of its Evolution of Flight Campaign.

Visit Italy on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on Italian pioneers.

From the collection of the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, Australia Born at Greenwich, England, in 1850, the second son of John Fletcher Hargrave and Ann, nee Hargrave, Lawrence was educated at Queen Elizabeth's School at Kirkby Lonsdale,

Westmoreland. At the age of 15 he sailed to Australia in the La Hogue to join his father, who had moved, to New South Wales in 1866 to pursue a legal career.

Born at Greenwich, England, in 1850, the second son of John Fletcher Hargrave and Ann, nee Hargrave, Lawrence was educated at Queen Elizabeth's School at Kirkby Lonsdale,

Westmoreland. At the age of 15 he sailed to Australia in the La Hogue to join his father, who had moved, to New South Wales in 1866 to pursue a legal career.

Lawrence was destined to follow in his father's career footsteps but he

failed his matriculation and in 1867 was apprenticed in the engineering workshops of the Australasian Steam Navigation Company. The cause of his failure is usually seen as his circumnavigation of Australia as a passenger in the schooner Ellesmere

soon after his arrival in the colony rather than spend time in study. The circumnavigation seems to have awakened in Lawrence an interest in exploration and scientific discovery because over the next decade he joined several expeditions to

New Guinea, beginning with the ill-fated journey of the brig Maria which sank with great loss of life off the coast of Queensland. He joined Macleay's Chevert expedition, leaving it prematurely to join Octavius Stone in the Ellengowan. Although

regarded as the expedition's engineer Hargrave made detailed notes of his observations of people, their homes, habits, technology, and language. His last expedition to New Guinea was as engineer to the Italian naturalist, Luigi Maria d'Albertis

aboard the launch Neva. Hargrave mapped the Fly River and collected specimens of scientific interest. He was forced to surrender these specimens to d'Albertis.

Upon his return to Sydney he was employed briefly in the foundries of

Chapman & Company before becoming an 'extra observer' at the Sydney Observatory measuring double stars, observing the transit of Venus and making observations on the atmospheric consequences of the Krakatoa eruption.

Following

the death of his father Lawrence inherited a considerable landholding on the south coast of New South Wales which gave him a sizeable income. He resigned from the observatory to concentrate on his scientific experiments into animal motion

as a means of ship propulsion. This led him to consider the nature of locomotion through air in the pursuit of the proof of his 'trochoided plane' theory. He built a number of ornithopters which were tested from the veranda of his Sydney house.

These early ornithopters were powered by rubber bands but he realised that greater and more sustained power was required for a man-powered flying machine to succeed. He began experiments to develop a successful aeronautical engine.

In his search he discovered the rotary radial principle and built a model engine to prove its value.

Hargrave did not patent any of his inventions, preferring to disseminate all information to assist aviation experimenters throughout

the world. He became well-known throughout the United States, England and Europe as a contributor to the search for the successful aeroplane.

Due to increases in his family and hence costs, allied with the need to find an area with

winds favourable to his new line of experimentation, kites, Hargrave moved to Stanwell Park, south of Sydney. Here he designed and built a great variety of kites, ultimately finding that his box or cellular arrangement was the most efficient

and stable. He tested these kites by connecting four together and going aloft for a brief tethered 'flight' over Stanwell Park Beach on 12 November 1894. Once this information was disseminated there appears to have been an improvement in the

experimentation in aeronautics. The stability of the box kite translated into glider form gave some early aeronauts the ability to go aloft long enough to gain practical experience of the effects of wind and gusts on their machines. The flying

machines of Otto Lilienthal, which caught the imagination of many aviation pioneers as well as the general public, were unstable and difficult to control. It is noteworthy that the earliest successful aircraft such as Voisin and Chanute gliders

and the Wright aircraft seems to owe more to the box kite in appearance than to the batwing platform of the Lilienthal gliders. It is well attested that the design of the first successful aircraft in Europe, Santos-Dumont's 14-bis, was a construction

based on Hargrave's box kites. Similarly, there is no question of Hargrave's influence on the Voisin and Farman powered aircraft of the early years of the 20th century. However, a question still remains about the exact influence of Hargrave

on Octave Chanute and his gliders and the Wright brothers and their aircraft.

After the first successful flight of the Wright brothers in 1903 Hargrave continued with his aeronautical experiments but, in the later years, prior to

1914, spent more time assisting his son Geoffrey with his work on aircraft engines. Geoffrey was killed at Gallipoli in May 1915 and Lawrence succumbed to peritonitis in July of that year.

Many of his models were sent to the Deutsches

Museum in Munich and his letters, drawings and diaries sent to the Royal Aeronautical Society in London. Unfortunately many of the models were destroyed during WW2 but those that survived were returned to Sydney in the 1960s and the letters,

drawings and diaries later joined these. The Hargrave Collection, so called, is now held in the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney.

During his lifetime Lawrence Hargrave was regarded as one of the great pioneers of aviation. Researchers

such as Alexander Graham Bell sought him out and he corresponded with most of the serious aviation experimenters of the time. The indices to his correspondence read like a who's who in aviation in the late 19th century to early 20 century.

Author: Ian Debenham, Curator, Transport, Powerhouse Museum

Copyright © 2000 by Ian Debenham. Published on the web by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc., with permission.

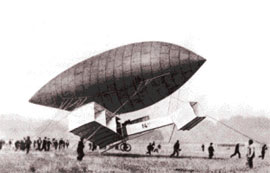

Born in the village of Cabangu, Brazil, 20 July 1873.

Died 23 july 1932. Alberto Santos-Dumont was born on 20

July 1873, in the village of Cabangu, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. at the age of 18, his father sent Santos-Dumont to Paris where he devoted his time to the studies of chemistry, physics, astronomy and mechanics. he had a dream and an objective:

to fly. in 1898, Santos-Dumont went up in his first balloon. it was round and unusually small and he called it brésil (brazil). however, it was capable of lifting a payload of 114.4 lb, and had in its lower part a wicker basket. his second

balloon, "america," had 500 m3 of capacity and gave Santos-Dumont the aero club of paris' award for the study of atmospheric currents. twelve balloons participated in this competition but "america" reached a greater altitude and remained in the

air for 22 hours. between 1898 and 1905 he built and flew 11 dirigibles. contrary to the prevailing common sense at that time, he employed in his lighter-than-air aircraft piston-powered engines with the lifting-gas hydrogen. he won the deutsch

prize, which was conceived and granted by the oil tycoon deustch de la merthe, when for the first time in the history a dirigible went around the eiffel tower on october 19th, 1901. this prize amounting 100,000 francs stipulated a dirigible ride

comprised of a flight with takeoff and landing at the saint-cloud field with a total duration of 30 minutes, including the going around the eiffel tower. in 1904, Santos-Dumont came to the united states and was invited to the white house to meet

president theodore roosevelt, who was very interested in the possible use of dirigibles in naval warfare. the interesting thing is that santos-dumont and the wright brothers never met, even though they had heard of each other's work.

Alberto Santos-Dumont was born on 20

July 1873, in the village of Cabangu, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. at the age of 18, his father sent Santos-Dumont to Paris where he devoted his time to the studies of chemistry, physics, astronomy and mechanics. he had a dream and an objective:

to fly. in 1898, Santos-Dumont went up in his first balloon. it was round and unusually small and he called it brésil (brazil). however, it was capable of lifting a payload of 114.4 lb, and had in its lower part a wicker basket. his second

balloon, "america," had 500 m3 of capacity and gave Santos-Dumont the aero club of paris' award for the study of atmospheric currents. twelve balloons participated in this competition but "america" reached a greater altitude and remained in the

air for 22 hours. between 1898 and 1905 he built and flew 11 dirigibles. contrary to the prevailing common sense at that time, he employed in his lighter-than-air aircraft piston-powered engines with the lifting-gas hydrogen. he won the deutsch

prize, which was conceived and granted by the oil tycoon deustch de la merthe, when for the first time in the history a dirigible went around the eiffel tower on october 19th, 1901. this prize amounting 100,000 francs stipulated a dirigible ride

comprised of a flight with takeoff and landing at the saint-cloud field with a total duration of 30 minutes, including the going around the eiffel tower. in 1904, Santos-Dumont came to the united states and was invited to the white house to meet

president theodore roosevelt, who was very interested in the possible use of dirigibles in naval warfare. the interesting thing is that santos-dumont and the wright brothers never met, even though they had heard of each other's work.

Alberto Santos-Dumont at the helm of one of his airships. |

Santos-Dumont going around the Eiffel Tower with its No. 6 |

Louis Cartier invented the wristwatch for his famous friend, Alberto Santos-Dumont, in march of 1904. they had met and become good friends in 1900. Santos-Dumont's deustch prize conquest was celebrated at maxim's that evening, and at some point

Santos-Dumont complained to cartier about the difficulty of checking his pocket watch to time his performance. he wanted his friend to come up with an alternative that would permit him to keep both hands on the controls. louis cartier went to

work on the idea and the result was a watch with a leather band and a small buckle, to be worn on the wrist. santos-dumont never took off again without his personal cartier wristwatch.

Santos-Dumont also designed a helicopter, the

picture of which was displayed on the cover page of the periodic "la vie au grand air" of january 12, 1906. due to technical difficulties to put such machine airborne, Santos-Dumont pursued his dream of flying with a winged aircraft, instead.

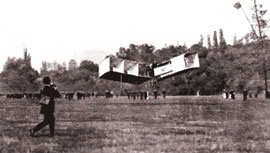

in 1906, santos-dumont took the nacelle of his dirigible balloon no. 14 and added to it a fuselage and biplane wings, whose cellular structure resembled the kites still found nowadays in japan. an antoinette v8 engine of 24 hp power was installed

ahead of the wings, driving a propulsion propeller; the airplane flew rear-first and was denominated 14-bis (since it was descendent of the dirigible balloon no. 14). it had a wingspan of 12 m and 10-m-long fuselage, and had a tricycle fixed landing

gear. santos-dumont developed what has to be called the first flight simulator, using winches and gears to let the 14-bis roll down a plan, while he learned how to control the plane. on 21 august 1906, santos-dumont made his first attempt to fly.

he did not succeed, since the 14bis was underpowered. on september 13th, with a reengined 14bis (now with a 40 or 50 hp power engine which he obtained through louis bréguet), Santos-Dumont made the first flight of 7 or 13 m (according to

different accounts) above the ground, which ended with a violent landing, damaging the propeller and landing gear. on october 23th, 1906 his 14bis biplane flew a distance of 60 meters at a height of 2 to 3 meters during a seven-sec-long flight.

Santos-Dumont won the 3,000 francs prize archdeacon, instituted in july 1906 by the american ernest archdeacon, to honor the first flyer to achieve a level flight of at least 25 m. before his next flight santos-dumont modified the 14-bis by the

addition of large hexagonal ailerons, to give some control in roll. since he already had his hands full with the rudder and elevator controls (and could not use peddles since he was standing), he operated these via a harness attached to his chest.

if he wanted to roll right he would lean to his right, and vice versa. one witness likened santos-dumont's contortions while flying the 14-bis to dancing the samba! with the modified aircraft, he returned to bagatelle on 12 november. this time

the brazilian made six increasingly successful flights. one of these flights was 21,4 sec long within a 220 m path at a height of 6 m. the brazilian always used his cartier wristwatch to check the duration of his flights. the flight experiments

with the 14bis took place at le bagatelle (air)field in paris. Santos-Dumont did not employ any catapult or similar device to place his craft aloft. as far as the world knew, it was the first airplane flight ever and santos-dumont became a hero

to the world press. the stories about the wright brothers' flights at kitty hawk and later near dayton, ohio, were not believed even in the us at the time.

The dirigible no. 14 and the 14b during trials to evaluate its flight characteristics. Source: Museu Aeroespacial, Rio de Janeiro |  The first sustained flight of a fixed-wing craft took place on 23 October 1906 in France. Source: Museu Aeroespacial, Rio de Janeiro. |

The Brazilian aviation pioneer continued with his experiments, building other dirigible balloons, as well as the aircraft no. 19, initially called Libellule (later changed to Demoiselle) in 1907. It was a small high-wing monoplane, with only

5.10 m wingspan, 8 m long and weighing little more than 110 Kg with Santos Dumont at the controls. With optimum performance, easily covering 200 m of ground during the initial flights and flying at speeds of more than 100 km/h. Dumont used to

perform flights with the airplane on Paris and some small trips for nearby places. The Demoiselle was the last aircraft built by Santos Dumont and the type suffered several modifications from 1907 to 1909. Santos Dumont was so enthusiastic about

the aviation that he released the drawings of Demoiselle for free, thinking that the aviation would be the mainstream of a new prosperous era for the mankind. Clément Bayard, an automotive maker, constructed several units of Demoiselle.

Dumont retired from his aeronautical activities in 1910. Alberto Santos Dumont, seriously ill and disappointed, it is said, over the use of aircraft in warfare, committed suicide in the city of Guarujá in São Paulo on July 23, 1932.

His numerous and decisive contributions to aviation are his legacy to mankind.

The 14Bis flying on 12 November 1906. The new ailerons are clearly visible. Source: Museu Aeroespacial, Rio de Janeiro. |  The successful Demoiselle monoplane, which Santos-Dumont employed as private transport. Source: Museu Aeroespacial, Rio de Janeiro |

Visit the Brazil Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on Brazilian pioneers.

Provided to the AIAA for the purpose of its Evolution of Flight Campaign.

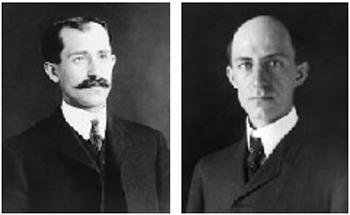

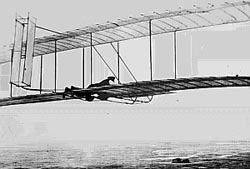

Wilbur: born near Millville IN, 16 April 1867. Died 30 May 1912.

Orville: born in Dayton OH, 19 August 1871. Died 30 January 1948.  On 17 December 1903, at Kitty

Hawk, North Carolina, Orville and Wilbur Wright realized one of mankind's earliest dreams – they flew! Although balloons and gliders existed, the Wrights made the world's first successful sustained and controlled flight of a man-operated,

motor-driven aircraft.

On 17 December 1903, at Kitty

Hawk, North Carolina, Orville and Wilbur Wright realized one of mankind's earliest dreams – they flew! Although balloons and gliders existed, the Wrights made the world's first successful sustained and controlled flight of a man-operated,

motor-driven aircraft.

Sons of a clergyman, their mechanical abilities surfaced at an early age, and they shared similar interests, becoming inseparable. Neither one ever married. The brothers opened a bicycle shop in 1892 and were

soon manufacturing their own wheeled creations.Even as youngsters they were fascinated with flight, playing with kites and a toy helicopter. The glider flights of Otto Lilienthal attracted their interest, as well as experiments by Octave Chanute

and Samuel Langley. By observing how buzzards maintained balance while soaring, wilbur was first to realize that an airplane had to operate on three axes to fly successfully. In 1900 they

built their first of several gliders, a biplane that soared for 300'. In 1901, using aerodynamics tables compiled by Langley and Lilienthal, they constructed new wings for a larger glider. however, its flight was marginal, so they challenged the

accuracy of the tables by analyzing 200 model wings in a small, home-made wind tunnel. the tables proved to be wrong, and the Wrights painstakingly computed new ones. Using this information, their 1902 glider had almost double the efficiency of

their previous ones, and at Kitty Hawk that year made more than 1,000 flights.

In 1900 they

built their first of several gliders, a biplane that soared for 300'. In 1901, using aerodynamics tables compiled by Langley and Lilienthal, they constructed new wings for a larger glider. however, its flight was marginal, so they challenged the

accuracy of the tables by analyzing 200 model wings in a small, home-made wind tunnel. the tables proved to be wrong, and the Wrights painstakingly computed new ones. Using this information, their 1902 glider had almost double the efficiency of

their previous ones, and at Kitty Hawk that year made more than 1,000 flights.

By the end of 1902 they were ready to begin work on a powered machine. With their mechanic, Charles Taylor, they designed and built an engine with the necessary

lightness and power-12hp at 1200 rpm, weighing 170 pounds -- and hand-carved two efficient propellers. in 1903, with a strong wind at Kitty Hawk, the Wrights tested the flyer. Orville, as pilot, lay alongside the motor on the lower wing while

his brother steadied the craft at one wingtip. After a 40' run the plane became airborne, and in the 12 seconds before it touched the ground it flew for 120'. Wilbur later piloted the longest flight of that day, 852' in 59 seconds.

Returning

to Ohio, the brothers began experimenting with new planes and motors and flew an improved Flyer II at Huffman Prairie near Dayton in 1904. In 1905, the Flyer III became the world's first practical airplane, one that could turn, bank, fly figure-eights,

and remain airborne for more than half an hour. Yet they attracted little attention. After more than 200 flights in 1904 and 1905, a patent was granted for the airplane on 22 May 1906, but it was not until 1908 that they began to receive credit

and attention for their invention. Submitting a bid to the Army for a military flying machine, Orville brought a Flyer to Fort Myers, Virginia in 1908, passed the trials and won a contract for the world's first military airplane. Later that year,

his plane crashed after a propeller failure, seriously injuring him and killing his passenger, Lt. Thomas Selfridge.  Wilbur died of typhoid fever in

1912. Orville continued flying actively until 1915, when he sold his interest in the Wright Company, then retired to serve on the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, and for years argued with officials of the Smithsonian Institution over

whether the Wrights or Langley had built the first successful plane. Angry about their championing Langley's "swan dive" as an actual first flight, he loaned Flyer I to London's Kensington Museum in 1928. In 1942, Smithsonian officials made a

public apology, but it wasn't until after Orville died that Flyer I was finally returned for permanent display at what is now the National Air and Space Museum.

Wilbur died of typhoid fever in

1912. Orville continued flying actively until 1915, when he sold his interest in the Wright Company, then retired to serve on the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, and for years argued with officials of the Smithsonian Institution over

whether the Wrights or Langley had built the first successful plane. Angry about their championing Langley's "swan dive" as an actual first flight, he loaned Flyer I to London's Kensington Museum in 1928. In 1942, Smithsonian officials made a

public apology, but it wasn't until after Orville died that Flyer I was finally returned for permanent display at what is now the National Air and Space Museum.

Visit the United States Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on American pioneers.

Provided to the AIAA for the purpose of its Evolution of Flight Campaign.

Biography Courtesy of AeroFiles.

Photo courtesy of Patty Wagstaff Airshows Inc.  Patty Wagstaff flies one of the most thrilling, low-level

aerobatic routines in the world today. Flying before millions of air show spectators each year, her breathtaking performances give spectators a front-row seat view of the precision and complexity of modern, unlimited hard-core aerobatics. Her

aggressive smooth style sets the standard for performers the world over.

Patty Wagstaff flies one of the most thrilling, low-level

aerobatic routines in the world today. Flying before millions of air show spectators each year, her breathtaking performances give spectators a front-row seat view of the precision and complexity of modern, unlimited hard-core aerobatics. Her

aggressive smooth style sets the standard for performers the world over.

Born 11 September 1951, in St. Louis, Missouri, Patty moved to Japan when she was nine years old where her father was a captain for Japan Air Lines. Her cross-cultural

academic career began in Japan, took her to Southeast Asia and Europe and then a six-year work-study program in Australia. She moved to Alaska in 1979 where she began her now-legendary career in aviation. Patty's first flying lesson was in a Cessna

185 floatplane and since then she has earned her Commercial, Instrument, Seaplane and Commercial Helicopter Ratings. She is a Flight and Instrument Instructor and is rated and qualified to fly many airplanes, from World War II warbirds to jets.

Her sister, Toni, is also a pilot and a captain for Continental Airlines based in Guam.

Patty's skill is based on experience. She is a six-time member of the U.S. Aerobatic Team that competes in Olympic-level international competition,

and the highest-placing American with gold, silver and bronze medals, a three-time U.S. National Aerobatic Champion, an IAC Champion, and a six-time recipient of the "First Lady of Aerobatics" Betty Skelton Award. The first woman to win the title

of U.S. National Aerobatic Champion, Patty has won the gold, silver and bronze medals in National as well as International Competition. She has trained with the Russian Aerobatic Team and has flown air shows and competitions in such exotic places

as Russia, South America and Europe.

In March, 1994, her airplane, the Goodrich Extra 260, went on display in the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum in Washington DC. You can see Patty's airplane and exhibit in the Pioneers

of Flight Gallery right next to Amelia Earhart's Lockheed Vega.

Patty has won many awards for her flying and is particularly proud of receiving the air show industry's most prestigious award, the "Sword of Excellence," as well as the

"Bill Barber Award for Showmanship" and is the 1996 recipient of the "Charlie Hillard Award."

Patty Wagstaff Airshows, Inc. is based in St. Augustine, Florida. During the off-season Patty engages in such diverse projects as stunt flying

and coordination for the movie and television industry, and is a member of the Screen Actors Guild, the Motion Picture Pilots Association and the United Stuntwomen's Association. She has "demoed" airplanes for companies such as Raytheon flying

their new military trainer, the T-6A Texan II in airshows, and recently has been in Africa working with the Kenya Wildlife Service giving recurrency and bush training to their pilots in Kenya.

Her latest venture, Patty Wagstaff Airshows, is the premier site for aerobatic enthusiasts.

Achievements:

1998 Bill Barber Award for Showmanship

1997 Inductee, Arizona

Aviation Hall of Fame

1997 Recipient, NAA Paul Tissiander Diploma

1997 Inductee, Women in Aviation International Hall of Fame

1996 Recipient, Charlie Hillard Trophy

1996 GAN & Flyers Readers Choice Award, Favorite Female

Performer

1996 Top Scoring US Pilot at World Aerobatic Championships

1995 Recipient, ICAS Sword of Excellence Award

1994 National Air and Space Museum Award for Current Achievement

1994 NAA Certificate of Honor

1994/1992/1990

Top US Medal Winner, World Aerobatic

Championships

1993 International Aerobatic Club Champion

US National Aerobatic Champion - 1993, 1992, 1991 US National Aerobatic Championships

1991 Voted Western Flyer

Reader's Choice Favorite Airshow Performer

1988-1994 Winner Betty Skelton "First Lady of Aerobatics" Trophy

1987 Rolly Cole Memorial Award for Contributions to Sport Aerobatics

1985-1996 Member, U.S. Aerobatic Team

Visit

the United States Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on American pioneers.

Biography Courtesy of Patty Wagstaff Airshows, Inc.

Born at Paris, France, 18 February 1832.

Died 23 November 1910.  Octave Alexandré Chanute began his career in

railroad construction at the Hudson River Railroad in Ossining, New York. A self-taught engineer, he became a legend for his novel designs and construction of complex bridges and railroad terminals. Experiments in material preservation led to

his invention of the system for pressure treating rail ties and telephone poles with cresote, techniques still in use worldwide.

Octave Alexandré Chanute began his career in

railroad construction at the Hudson River Railroad in Ossining, New York. A self-taught engineer, he became a legend for his novel designs and construction of complex bridges and railroad terminals. Experiments in material preservation led to

his invention of the system for pressure treating rail ties and telephone poles with cresote, techniques still in use worldwide.

In 1889, at age 57, he began his second career and devoted himself to the solution of the problems of

flight. In typical Chanute fashion of step-by-step investigation, his first act was to assemble all known data on the science into a single synthesis and to catalogue its problems. Initial objectives were the elimination of the errors of experimentalists

and to advance the science of flight by making known both their successes and failures through his publication of the classic book, "Progress in Flying Machines." In 1894, he gave the world its first compendium on flight, and earned himself the

title of the world's first aero historian.

Chanute believed the advancement of flight science must be the work of many. He corresponded internationally and encouraged the pioneers: Voisin, Blériot, Farman, and the Wright Brothers,

of whom he was a special friend and mentor. He sought no patents on his inventions, and gave his findings openly to all. His sponsorship of the term "aviation" resulted in its common use.

Gliding experiments on the shores of Lake Michigan

in the 1890's contributed much to flight science in the areas of control systems and stability, efficiency of materials, aircraft structural integrity and strength. In utilizing his knowledge of braced-box-structure in bridge construction, he

invented the familiar strut-wire-braced wing structure still employed in biplane aircraft. Wilbur Wright, in his 1911 eulogy of Chanute, said, "His labors had vast influence in bringing about the era of human flight."

Visit the France

Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on French pioneers.

Provided to the AIAA for the sole purpose of its Evolution of Flight Campaign.

Biography Courtesy of AeroFiles.

Born in Triflis, Russia, 7 June 1894.

Died 24 August 1974.  After acquiring an aeronautical engineering

degree, Alexander Prokofieff de Seversky was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Imperial Navy of Russia in 1915. On his first combat mission he lost his right leg. Less than a year later he was back in the air, flying 57 missions, and downing

13 German aircraft to become Russia's top Naval Ace.

After acquiring an aeronautical engineering

degree, Alexander Prokofieff de Seversky was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Imperial Navy of Russia in 1915. On his first combat mission he lost his right leg. Less than a year later he was back in the air, flying 57 missions, and downing

13 German aircraft to become Russia's top Naval Ace.

In 1917 de Seversky came to the USA, offering his services to the War Dept, making outstanding contributions to their production of the British-designed SE-5 fighter and serving

as a test pilot. In 1921 he and General Billy Mitchell worked together staging the bombing tests that graphically demonstrated the vulnerability of battleships to airplanes. Then, following his invention of the in-flight refueling method, he worked

with the Sperry Gyroscope Company, to produce a gyro-stabilized bombsight in 1923 that was acclaimed the world's best. He was commissioned a major in the USAAC, and founded Seversky Aircraft Corp in 1928.

In 1930 de Seversky again made

a most important contribution to his new country's air efforts in the all-metal P-43 fighter, predecessor of the historic P-47 Thunderbolt. Many of its new concepts are universally accepted construction principles for today's aircraft. Capable

of speeds over 300 mph, the P-43 gave long-range and high-altitude protection to US bombers. He also developed an advanced design amphibian in which he set world speed records 1933-35, and an all-metal monoplane that set speed records at the 1933-39

Nationals, as well as a transcontinental speed record in 1938.

The outbreak of WW2 found our air arsenal pitifully neglected. To bring the magnitude of this problem to public attention, de Seversky wrote his best-seller book, "Victory

Through Airpower." Also made into a movie, it awoke people to the need for better airpower. For that, and for his counsel on the strategic use of air power, President Truman awarded him the Medal of Merit.

By then he had become world

renown as an expert in the areas of airpower and defense. His Seversky Electroatom Corp of 1952 directed its efforts to defending the USA against nuclear attack, and to extraction of radioactive particles from the air. Research in that area led

to the discovery of the Ionacraft, an aircraft that derived lift and propulsion from ionic emissions. For serving as a special consultant to the Chiefs of Staff of the USAF, he received the Exceptional Service Medal in 1969. De Seversky was enshrined

in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1970.

Visit the Russia Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on Russian pioneers.

Provided to the AIAA for the sole purpose of its Evolution of Flight Campaign.

Biography Courtesy

of AeroFiles.

Otto Lilienthal, a German civil engineer, was born in 1848 at Anklam, Pomerania. His practical experiments began when, at

the age of thirteen, he and his brother Gustav made wings of common materials. These wings consisted of a wooden framework covered with linen, which Otto attached to his arms, and then ran downhill flapping them.

Otto Lilienthal, a German civil engineer, was born in 1848 at Anklam, Pomerania. His practical experiments began when, at

the age of thirteen, he and his brother Gustav made wings of common materials. These wings consisted of a wooden framework covered with linen, which Otto attached to his arms, and then ran downhill flapping them.

In 1867, the two brothers

began seriously experimenting with wings. These wings the brothers fastened to their backs, moving them with their legs after the fashion of one attempting to swim. Before they had achieved any real success in gliding, the Franco-German war began.

Both brothers served in this campaign, resuming their experiments in 1871 at the conclusion of hostilities.

From 1871 onward, Otto Lilienthal (Gustav's interest in flying was not maintained) made what is probably the most detailed and accurate series of observations about the properties of curved wing surfaces. So far as could be done, Lilienthal

tabulated the amount of air resistance offered to a bird's wing, Through this he ascertained that the curve is necessary to flight because it offers far more resistance than a flat surface. In 1889 he published a work on the subject of gliding

flight which stands as data for investigators. He began to build his gliders and practice what he had preached, turning from experiment with models to wings that he could use.

In the summer of 1891, he built his first glider of rods

of peeled willow, over which was stretched strong cotton fabric. With this, Otto Lilienthal launched himself in the air from a springboard, making glides which, at first of only a few feet, gradually lengthened. As his experience progressed, he

gradually altered his designs. By 1895, Lilienthal had moved from his springboard to a conical artificial hill which he had had thrown up on level ground at Grosse Lichterfelde, near Berlin. This hill was made with earth taken from the excavations

incurred in constructing a canal, and had a cave inside in which Lilienthal stored his machines. Lilienthal made over 2,000 gliding flights between 1891 and 1896.

The fatal flaw of Lilienthal's gliders was lack of control. The crafts

were balanced by Lilienthal shifting his weight. By shifting his weight, he had to react to the movements rather than direct them. Despite his lack of control, Lilienthal flew his gliders well and he was dubbed the first flying man. He was well

known for his ability to glide for distances up to 1,000 feet.

It was Lilienthal's lack of control that ended his lifelong fascination with flight. On 8 August 1896, he crashed in a glider from a height of over 50 feet. He died soon

after. His careful notes and studies on glider flight would inspire many future pioneers of flight.

Visit the Germany Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on German pioneers.

Born Kiev, Russia, 2 May 1889.

Died 26 October 1972.  Learning of the works of the Wright brothers and Count Zeppelin, Igor Sikorsky's

interest in aviation was kindled as a boy. He graduated from Petrograd Naval College, studied engineering in Paris, and returned to Kiev in 1907 to enter Polytechnical Institute. In 1909, he went back to Paris-then the aeronautical center of Europe-to

learn more about the fascinating science of flight. Having learned what he could of aviation as it was then known in Europe, he bought an Anzani engine and went home to begin construction of a rotary-wing aircraft.

Learning of the works of the Wright brothers and Count Zeppelin, Igor Sikorsky's

interest in aviation was kindled as a boy. He graduated from Petrograd Naval College, studied engineering in Paris, and returned to Kiev in 1907 to enter Polytechnical Institute. In 1909, he went back to Paris-then the aeronautical center of Europe-to

learn more about the fascinating science of flight. Having learned what he could of aviation as it was then known in Europe, he bought an Anzani engine and went home to begin construction of a rotary-wing aircraft.

His first attempts

failed due to a lack of power and an understanding of the complex rotary-wing art. Undaunted, he turned his efforts to conventional aircraft and found success with the S-2, the second airplane of his design and construction. His fifth airplane,

the S-5, brought him national recognition as well as FAI pilot license Number 64. In 1912 his S-6-A received the highest award at Moscow's Aviation Exhibition, and that year his aircraft won first prize in military competitions at Petrograd. This

led to a position as head of the aviation subsidiary of the Russian Baltic Railroad Car Works, where, as a result of clogged carburetor and subsequent engine failure, he conceived the idea of an aircraft having more than one engine-a radical idea

at the time. The result of this was an engineering project that gave the world its first multi-engine airplane, the four-engined "Grand." This revolutionary aircraft also offered an enclosed cabin, upholstered chairs, lavatory, even an exterior

catwalk on the fuselage where passengers could walk while in flight.

There followed an even bigger aircraft, Ilia Mourometz, named for a legendary tenth-century folk hero. More than 70 military versions of the Ilia Mourometz were built for use as bombers during The World War. The Revolution ended Mr.

Sikorsky's career in Russian aviation, and he immigrated to France, then to the USA in 1919. Unable to find a position in aviation he resorted to teaching and lecturing in New York, mostly to fellow emigrants. Then some students and friends who

knew of his reputation in Russia pooled their resources in 1923 to fund the Sikorsky Aero Engineering Corporation.

The first product from the young and financially shaky concern was the S-29-A ("A" for America), a twin-engine, all-metal

transport which proved a forerunner of the modern airliner. Other aircraft designs followed, but the company achieved its most notable success with the twin-engine S-38 amphibian, which Pan American Airways used to open air routes to Central and

South America. Later, as a subsidiary of United Aircraft Corporation, the company operated the luxurious Flying Clippers which pioneered commercial air transportation across both oceans. The last Sikorsky flying boat, S-44, would for years hold

the record for fastest transatlantic flight.

The dormant concept of the helicopter resurfaced, and Sikorsky turned once again to notes and sketches he had jotted down for possible designs, some of which were patented. On 14 September

1939, he took his VS-300 a few feet off the ground to give the western hemisphere its first practical helicopter, the child from which today's helicopter industry grew. Military contracts followed and, in 1943, large-scale manufacture made the

R-4 the world's first production helicopter.

Awards and honors accorded to Igor Sikorsky would fill many pages, and include the National Medal of Science, the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy, the Collier Trophy, the USAF Academy's

Thomas D. White National Defense Award, the Guggenheim Medal, and the Royal Aeronautical Society's Silver Medal. He was inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame in 1968.

Even after his retirement in 1957 at age 68, Sikorsky continued

to work as an engineering consultant for his company, and was at his desk the day before he died.

Visit the Russia Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on Russian pioneers.

Provided to the AIAA for the sole purpose of its Evolution

of Flight Campaign.

Biography Courtesy of AeroFiles.

Image Courtesy of Calderara/Marchetti/LoGisma Editore Mario Calderara was born in Verona 10 October 1879, the elder son of an

army officer, Marco, and Eleonora Tantini. Marco Calderara (1848-1928) reached the rank of general of the "Alpini" corps. Eleonora Tantini died at the age of fifty, when Mario was 21 year old.

Mario Calderara was born in Verona 10 October 1879, the elder son of an

army officer, Marco, and Eleonora Tantini. Marco Calderara (1848-1928) reached the rank of general of the "Alpini" corps. Eleonora Tantini died at the age of fifty, when Mario was 21 year old.

Since his early childhood Mario was attracted

by life at sea. In 1898 he entered the Naval Academy in Livorno, and graduated as a midshipman in 1901. During his Livorno years he was known by his classmates for always dreaming about human flight, something which was totally unknown in those

days, except for the successful gliding flights of Otto Lilienthal (who fell to his death in 1896) and the aborted powered flight of Clement Ader in France. Mario's classmates were joking about his flying mania, and one of them made a sketch of

Calderara on a flying machine, crashing to the ground and being carried to a hospital, and then to a cemetery.

In 1905, Mario Calderara wrote to the Wright brothers in Dayton Ohio, after hearing about their successful attempts at flying

(a documented record of their flights was known only after 1905). He asked them about technical details and was pleasantly surprised when he received a satisfactory answer from Wilbur and Orville, as well as from F.C. Bishop, president of Aeroclub

of the United States. This correspondence continued during the following years and formed the basis of a friendship, which lasted throughout his entire life. Calderara had already made some experiments in 1903 and 1904 with primitive gliders,

and had studied the behavior of a flat surface on an incline calculating its coefficient of resistance to the wind (together with the Italian engineer Canovetti, he utilized the funicular from Como to Brunate as a slope for making his calculations).

After having received information from the Wright brothers, Mario Calderara requested permission from the Italian Navy to carry out some gliding experiments on water, towed by a motorboat. Permission was granted in 1906, and in the

spring of 1907 he started his first gliding experiments, in the gulf of La Spezia, with a "flying machine" inspired from the Wright biplane. At first he placed the glider on floaters, and held it with ropes, which would gradually release the glider

allowing a controlled lift. He ultimately installed his machine directly on the deck of the destroyer "Lanciere" and attempted to soar at a much higher height, taking advantage of the warship's higher speed. He did reach a height of more than

fifteen meters, but when the destroyer made a sharp turn to the left, the glider lost its balance and dived into the water. Calderara was dragged underwater by the glider's steel wires at a depth of more than three meters. He was carried to a

hospital half drowned and slightly wounded and was forbidden to continue his experiments, which were considered as too risky.

In 1908, the French pilot Leon Delagrange visited Rome in preparation for flight demonstrations. The airplane

manufacturer Gabriel Voisin accompanied him, and Mario Calderara asked Voisin if he could come to Paris and work in his shop as a draftsman and designer. Voisin agreed, and Calderara applied to the Italian Admiralty for a six months leave of absence

without pay. In July 1908 he traveled to Issy Les Moulineaux (near Paris) and worked in the shop of Gabriel Voisin (The two had become very good friends and collaborated on new ideas). After helping in the design of several airplanes, he was offered

by Mr. Ambroise Goupy, a wealthy Frenchman who was interested in flight, the opportunity of designing and manufacturing, funded by Goupy, a new type of flying machine, very light and small: a "tractor propelled biplane", the first of its type.

He built the airplane, called "Calderara Goupy" and flew it successfully on March 11th, 1909 in Buc (France).

In those months (summer 1908) Wilbur Wright had been invited to visit France and had been demonstrating the potentialities

of his marvelous "Flyer" which could carry out extended flights with a duration of thirty to sixty minutes, while the French airplanes manufactured by Blériot, Voisin and Farman could only stay in the air for a few minutes. The Italian

Aeroclub, acting in coordination with the Italian army's "Brigata Specialisti" headed by major Maurizio Moris, invited Wilbur Wright to Rome and offered to purchase one of his airplanes. Wilbur Wright was asked to train one or two Italian pilots

on the fields of Centocelle (Rome's future airport). Mario Calderara was selected as the first trainee, because he was the only person in Italy with the required references.

Wilbur Wright came to Rome in June 1909 and, after having

carried many VIPs as passengers on his machine, gave a few lessons to Mario Calderara and, in the last days, to army lieutenant Umberto Savoja, of the corps of engineers. Wilbur Wright left for the United States on May first, stating that Mario

Calderara was in a position to fly alone and to teach flying to lieut. Savoja. After his departure, Mario Calderara made many prolonged flights without any problems, but on a windy day, on May 6th, his airplane crashed and he was seriously wounded

(concussion of the brain). After recovering in the hospital, he managed to repair the Wright airplane with the assistance of Umberto Savoja, who was a very good engineer, and after a month and a half (July l909) he resumed the flights in Centocelle.

In September 1909, the Aeroclub of Italy called for an international air rally in Brescia (a similar rally had taken place in Reims, France, in July). Calderara was allowed to participate in this competition, which would be attended

by King Victor Emanuel in person. Three weeks before the rally, a violent tornado destroyed the canvas hangars built on the Brescia airport for the participants, and the Wright flyer, which had been already rebuilt in Rome, was damaged beyond

repair. The two officers (Calderara and Savoja) managed to rebuild the biplane in 9 days, using second quality wood and canvas, in time for the rally.

After mounting a new Italian motor, a "Rebus", on the flying machine, Mario Calderara

competed in all prescribed tests and won five out of eight prizes, which were being offered. The other Italian pilots who attempted to participate did not manage to lift their machines in the air, except Anzani on a French airplane, which crashed

beyond repair. The other pilots who flew successfully were the American Glenn Curtiss and the French Henry Rougier. The Brescia rally was a triumph for Calderara, who became a national hero overnight as the only Italian who could fly. He was awarded

Flying License n.1 by the Italian Aeroclub.

The famous Italian poet Gabriele d' Annunzio was interested in human flight and had come to Brescia hoping to be carried on an airplane as a passenger. He made a first aborted flight of a

few seconds with Glenn Curtiss and was disappointed; then asked Calderara, whom he had met in Centocelle, to carry him aloft. The latter accepted and took d'Annunzio on a ten minutes flight around the airport. D'Annunzio was elated and praised

emphatically Calderara's skills. At the time the poet was writing a novel about human flight, which revived the myth of Dedalus and Icarus. He made the hero of his book Paolo Tarsis temperamentally similar to Mario Calderara seen as a hard tempered

pilot with quick reflexes. Calderara's notoriety caused him to be subjected to repeated interviews by journalists, and his willingness to explain his flying technique was not appreciated by his direct superior in rank, major Moris who believed

this was not dignified on part of a career officer (This may have marked the beginning of a falling out between the two officers). During the next few months, Calderara underwent his exams for a graduate course in Livorno (which were required

for his promotion to Lieutenant) and was promoted with low grades because his flying had diverted him from his naval activities, and this damaged his career. Major Moris had accepted to utilize, after fitting it with a motor, his little airplane,

the Calderara Goupy biplane (which arrived from France without motor) for training Italian pilots. But in the fall of 1910, during Calderara' s absence the airplane, which had been stored in the Centocelle hangar was moved outside and left exposed

to bad weather. Soon rain and wind damaged the airplane beyond repair and it had to be demolished. This was a source of terrible disappointment for Calderara, who shortly afterwards was assigned to the Ministry of the Navy and was not utilized

anymore as an instructor for new pilots.

Calderara applied to the Admiralty for permission to build in La Spezia a new type of airplane in which could take off and land on water. Seaplanes did not exist at the time, except for a French

seaplane designed by Fabre, which had many drawbacks.

Calderara designed and built his seaplane, the largest flying machine in the world, in 1911, and flew it very successfully in the spring of 1912, carrying three passengers plus

the pilot in flight. He was invited to London, where he projected a film of his flights to a selected public which included the Honorable Winston Churchill.

World war one was approaching and the Italian Navy imposed on Mario Calderara

an interruption of his aeronautical activities, and a return to his naval assignments. During the war, Calderara was on board of several warships, and ultimately was in command of a torpedo ship in the Adriatic sea.

Towards the end

of 1917, the Admiralty entrusted him with the command of a new school for pilots of seaplanes to be located on the shore of the Bolsena lake, north of Rome. The trainees were American naval officers (America had just entered the war) and the school

was active throughout 1918 and until July 1919. Calderara's record in training the American pilots was considered as fully successful, with no casualties at all in 18 months, an exceptional demonstration of safety and skill in those days. The

U.S. Navy was impressed by the capacity of Lieut. Commander Calderara, and awarded him the American Navy Cross.

After the war, in 1923, Calderara was assigned to the Italian embassy in Washington as air attaché. He carried out

his task with the utmost skill and met many American statesmen, including president Coolidge and president-to-be Herbert Hoover. He also renewed contacts with his old friends of the pioneering days. He visited Glenn Curtiss and Orville Wright

and established new friendships with people involved with the aviation industry.

His assignment in Washington ended in 1925, and he decided to interrupt his career in the Italian Navy (in which he had attained the rank of commander).

He moved to Paris, France with his family and used Paris as a center for his new activity, representing several U.S. corporations, which manufactured airplane motors and instrument panels. His new work required a great deal of traveling in European

countries as well as the Soviet Union and Turkey.

His new activity was very successful, in spite of the 1929 crash of the Stock Exchange in New York. But a new world conflict was now approaching, and in 1939 Calderara had to move again

and seek protection in Italy. When war burst out, the house, which Calderara had bought near Paris, was expropriated as enemy property, and the family suffered further financial losses. In 1944, worn out by challenges as well as by his chain smoking

habit, Mario Calderara died suddenly in his bed. His beloved wife, countess Emmy Gamba Ghiselli, lived for 38 years after his death. She contributed substantially to the collection of documents, which constitute a heritage of Mario Calderara.

Visit the Italy Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on Italian pioneers.

©1999-2001 - Calderara/Marchetti/LoGisma Editore.

Born near Pensacola, FL, 11 May 1908 (estimated)

Died 7 August 1980.  Because Jacqueline Cochran was orphaned at

an early age, an exact date of birth is unknown. She grew up in poverty in a foster home, and reportedly selected her name from a telephone book. At eight she went to work in a cotton mill in Georgia, later was trained as a beautician and pursued

that career in Alabama, Florida, and New York City.

Because Jacqueline Cochran was orphaned at

an early age, an exact date of birth is unknown. She grew up in poverty in a foster home, and reportedly selected her name from a telephone book. At eight she went to work in a cotton mill in Georgia, later was trained as a beautician and pursued

that career in Alabama, Florida, and New York City.

Her most distinguished aviation career began in 1932 when she obtained her pilot's license at Long Island's Roosevelt Field with only three weeks of instruction. From that time, her

life was one of total dedication to aviation. In 1935, Cochran became the first woman to enter the Bendix Trophy Race, but her Northrop Gamma was plagued with engine problems. She married millionaire Floyd Odlum, and in 1937 again entered the

Bendix race in a Beechcraft 17, taking first place in the Women's Division and third overall flying from Los Angeles to Cleveland, also winning the Harmon Trophy for Outstanding Female Pilot for that year. In 1938 she won the Bendix flying a Seversky

P-35, becoming respected by all for her competitive spirit and high skill. Among her last flying activities was the establishment in 1964 of a record of 1,429mph in the F-104, prior to which she was the first woman to break the sound barrier,

flying an F-86.

At the beginning of WW2, she became a Wing Commander in the British Auxiliary Transport Service, ferrying US-built Hudson bombers to England, becoming the first female pilot to ferry a bomber across the Atlantic. At

the United States entry into the war, she offered her services to the USAAC and formed the famed Women's Air Force Service Pilots, and was appointed to the USAAF General Staff as director of the WASPs. This more than 1000-strong group played a

major role in delivering of aircraft to the combat areas throughout the world. For her service, Cochran was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal and USAF Legion of Merit, and became the first civilian female to be commissioned a lieutenant

colonel in the USAF Reserves. In 1958, she also became the first woman president of Federation Aeronautique International.

Some of the honors she has been accorded include the Harmon Trophy, the General William E. Mitchell Award, Federation

Aeronautique Gold Medal, and decorations from numerous countries. She was enshrined into the National Aviation Hall of Fame 1971 and invested in the International Aerospace Hall of Fame in 1965.

Visit the United States Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more

information on American pioneers.

Provided to the AIAA for the sole purpose of its Evolution of Flight Campaign.

Biography Courtesy of AeroFiles.

Photo Courtesy of International Women's Air and Space Museum.

Amelia Mary was born to Amy and Edwin Earhart in Atchison, Kansas on July 24, 1897. She attended Hyde Park High School in Chicago, Illinois, Ogontz School for Girls

in Rydal, Pennsylvania, and Columbia University in New York, New York to prepare for a career in Medicine and Social Science. She served during World War I as a military nurse in Canada where she developed an interest in flying. She pursued this

interest in California, receiving her pilot's license in 1922. Though she continued her association with aviation by entering numerous flying meets, she spent several years as a teacher and social worker at Dennison House, in Boston.

Amelia Mary was born to Amy and Edwin Earhart in Atchison, Kansas on July 24, 1897. She attended Hyde Park High School in Chicago, Illinois, Ogontz School for Girls

in Rydal, Pennsylvania, and Columbia University in New York, New York to prepare for a career in Medicine and Social Science. She served during World War I as a military nurse in Canada where she developed an interest in flying. She pursued this

interest in California, receiving her pilot's license in 1922. Though she continued her association with aviation by entering numerous flying meets, she spent several years as a teacher and social worker at Dennison House, in Boston.

Amelia Earhart gained considerable fame on June 17-18, 1928, as the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air. The Fokker trimotor piloted by Wilman Stutz and Louis Gordon flew from Trepassy Bay, Newfoundland, to Burry Port, Wales. However, on

this flight she would only serve as a passenger. She took the place of Amy Guest, the heir to a Pittsburgh steel fortune. Guest's family had forbidden her to make the trip so she had agreed to give up her seat to a women. Amelia jumped at the

chance.

In 1929 Earhart co-founded the "Ninety-Nines," an international organization of women pilots, which continues today to promote opportunities for women in aviation, and served from 1930 to 1932 as its first president.

In 1931, Amelia made changes in her personal and professional life. She married publisher George Putnam and went on to set an autogyro altitude record. The following year she again accomplished the Atlantic flight which brought her fame, this

time as a solo pilot flying from Harbor Grace, Newfoundland, to Londonberry, Ireland, a first for a women.

Amelia Earhart took an active role in efforts to open the field of aviation to women and end male dominance in this exciting

new field. She served as an officer of the Luddington line, which provided one of the first regular passenger services between New York and Washington, D.C. In January 1935, she outdid her Atlantic solo by making a solo flight from Hawaii to California,

a much longer distance than the Canada-England flight. She became the first pilot to successfully fly that route. Her numerous accomplishments earned her the Distinguished Flying Cross, the first women so designated by the United States Congress.

Amelia Earhart set out in June 1937 to circumnavigate the world. Accompanied by Fred Noonan, her navigator, Amelia Earhart flew her twin engine Lockheed Electra into one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the 20th century. On the

most difficult leg of the trip, Earhart and Noonan vanished near Howland Island in the Pacific. Intense searching by both the American and Japanese forces found no trace of Amelia Earhart, Fred Noonan, or their plane and fueled speculation as

to the reason for such a dangerous flight. Many argued that the flight was a reconnaissance flight to gather data on Japan prior to the United States entry into World War II. Many others, especially in the aviation community, held fast that Amelia

Earhart was driven by her passion for flying.

Though few facts are known about the July 2, 1937 disappearance in the central Pacific near the International Date Line, one thing is certain: Amelia Earhart had made a unique and timeless

contribution to aviation and to women in aviation which will go unparalleled for decades to come.

Visit the United States Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on American pioneers.

Provided to the AIAA for the sole purpose of its

Evolution of Flight Campaign.

Born 1894 in Hermannstadt, Austria-Hungary (now Sibiu, Romania) died 1989 in Feucht near Nuremberg, Germany

Born 1894 in Hermannstadt, Austria-Hungary (now Sibiu, Romania) died 1989 in Feucht near Nuremberg, Germany

Oberth grew up in the German-speaking part of

Transylvania in the Austro-Hungarian empire. In his youth he became interested in space travel by reading Jules Verne's novels. In 1913 he went to Munich to study medicine. His studies were interrupted by World War I, where Oberth served in the

Austro-Hungarian army in a medical corps.

After the war, Oberth studied physics and submitted in 1922 to the University of Heidelberg a thesis about rocket-propelled space travel. It was rejected because the idea of space travel was too utopian in academic circles. Shortly afterwards he published

his work as a small booklet "Die Rakete Zu Den Planetenršumen" (The Rocket Into Interplanetary Space) at his own expense. The book was a great success and got much publicity, despite the fact that it was written in a very technical language,

and it caused scientific discussions about a field, which was known only from fantastic (utopian, science fiction) literature. Between 1924 and 1938 Oberth worked as a teacher of mathematics and physics at a school in Mediasch, Transylvania but

stayed in touch with fellow rocketry pioneers through the German rocket society ("Verein Fÿr Raumschiffahrt").  In 1928/29 Oberth started to build a high altitude rocket for the occasion of the premiere of the movie "Die Frau In Mond" by the Austrian director Fritz Lang, for which he was scientific advisor.

In 1928/29 Oberth started to build a high altitude rocket for the occasion of the premiere of the movie "Die Frau In Mond" by the Austrian director Fritz Lang, for which he was scientific advisor.

During World War II Oberth worked at the Vienna and Dresden Universities of Technology and later became a consultant at the

PeenemŸnde rocket plant. During all his life Oberth was creatively working in the field of rocketry but never held any prestigious leading position within that field.

During World War II Oberth worked at the Vienna and Dresden Universities of Technology and later became a consultant at the

PeenemŸnde rocket plant. During all his life Oberth was creatively working in the field of rocketry but never held any prestigious leading position within that field.

Visit the Austria Profile on the History of Flight from Around the World page for more information on Austrian

pioneers and the Germany Profile for more information on German pioneers.

Editor's note:

Oberth's above mentioned Austro-Hungarian roots justified to include in the Austrian overview. However, it probably would

be more appropriate to refer to him as a German (with an Austro-Hungarian background). Still, the lack of German citizenship had an important disadvantageous influence on his career in Germany.

Provided to the AIAA for the sole purpose

of its Evolution of Flight Campaign.

Biography courtesy of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the European Space Technology Centre (Estec) Fine Arts Club.

Born in Wirsitz, Germany, 23 March 1912

Died in Alexandria, Virginia, 16 June 1977  Wernher von Braun was one of the world's first

and foremost rocket engineers and a leading authority on space travel. He was born March 23, 1912, in Wirsitz, Germany. His wife was Maria von Quirstorp von Braun. Together, they had three children named Iris, Magrit, and Peter. He became a U.S.

citizen on April 14, 1955. His interests and hobbies included: his family, space, rockets, scuba diving, boating, flying, reading, writing, music, and poetry.

Wernher von Braun was one of the world's first

and foremost rocket engineers and a leading authority on space travel. He was born March 23, 1912, in Wirsitz, Germany. His wife was Maria von Quirstorp von Braun. Together, they had three children named Iris, Magrit, and Peter. He became a U.S.

citizen on April 14, 1955. His interests and hobbies included: his family, space, rockets, scuba diving, boating, flying, reading, writing, music, and poetry.

Von Braun was a man of immense talent. He headed the development of the

Explorer satellites, the Jupiter and Jupiter-C rockets, and Pershing. He also headed the work on the Redstone rocket, Saturn rockets, and the Skylab, the world's first space station. He directed the technical development of the U.S. Army's ballistic

missile program at Redstone Arsenal.

Wernher von Braun was the second of three sons born to Baron von Braun and Baroness Emmy von Quistorp. His natural leadership and ability to encourage others led him to organize an observatory construction

team at the age of sixteen. Later he enrolled at the Berlin Institute of Technology in 1930. He received his bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering at the age of twenty and was offered a grant to conduct and develop scientific investigations

on liquid-fueled rocket engines. Two years later, von Braun received his Ph.D. in physics from the University of Berlin.

On June 20, 1945, Cordell Hull, the U.S. Secretary of State at the time, approved the transfer of von Braun's

team of German rocket specialists. This was known as Operation Paperclip because the paperwork of those selected to come to the U.S. was indicated by paperclips. They arrived in the United States at New Castle Army Base, just south of Wilmington,

Delaware. Then they moved to their new home at Fort Bliss, Texas, a large Army installation under the command of Major James P. Hamill. Here they were tasked to train military, industrial, and university personnel in rockets and guided missiles.

They were also to help refurbish, assemble, and launch a number of V-2's.

During this time von Braun proposed to 18-year-old Maria von Quirstorp in Germany by mail. They married on March 1, 1947. They had their first child, Iris, in

December 1948.

Between 1950 and 1956, von Braun led the Army's development team at Redstone Arsenal, resulting in the Arsenal's namesake, the Redstone rocket. Later they developed the Jupiter-C, a modified Redstone. This rocket successfully